Cyber Security Breaches Survey 2022

Updated 11 July 2022

Overview

The Cyber Security Breaches Survey is an influential research study for UK cyber resilience, aligning with the National Cyber Strategy. It is primarily used to inform government policy on cyber security, making the UK cyber space a secure place to do business. The study explores the policies, processes, and approaches to cyber security for businesses, charities, and educational institutions. It also considers the different cyber attacks these organisations face, as well as how these organisations are impacted and respond.

For this latest release, the quantitative survey was carried out in winter 2021/22 and the qualitative element in early 2022.

Responsible analyst: Maddy Ell

Responsible statistician: Robbie Gallucci

Statistical enquiries: evidence@dcms.gov.uk

General enquiries: enquiries@dcms.gov.uk

Media enquiries: 020 7211 2210

Key findings

Cyber attacks

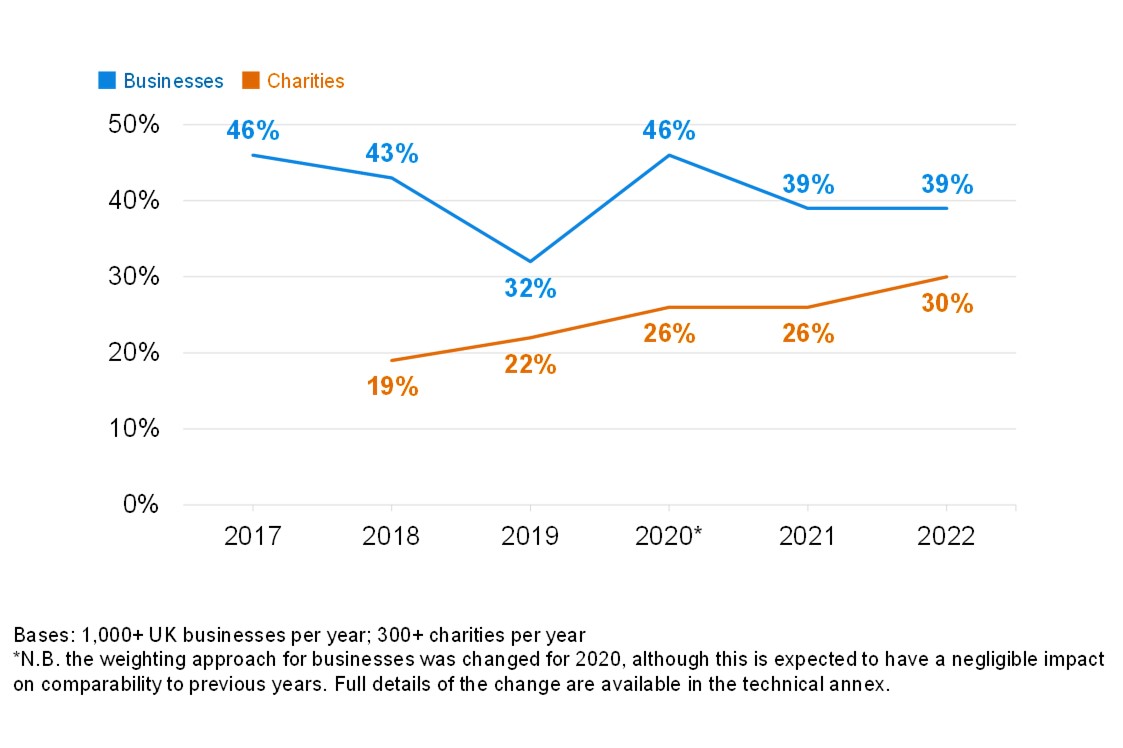

Our survey results show that in the last 12 months, 39% of UK businesses identified a cyber attack, remaining consistent with previous years of the survey. However, we also find that enhanced cyber security leads to higher identification of attacks, suggesting that less cyber mature organisations in this space may be underreporting.

Table 1.1: Proportion of UK businesses identifying cyber attacks each year

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46% | 43% | 32% | 46% | 39% | 39% |

Attack type

Of the 39% of UK businesses who identified an attack, the most common threat vector was phishing attempts (83%). Of the 39%, around one in five (21%) identified a more sophisticated attack type such as a denial of service, malware, or ransomware attack. Despite its low prevalence, organisations cited ransomware as a major threat, with 56% of businesses having a policy not to pay ransoms.

Frequency & impact

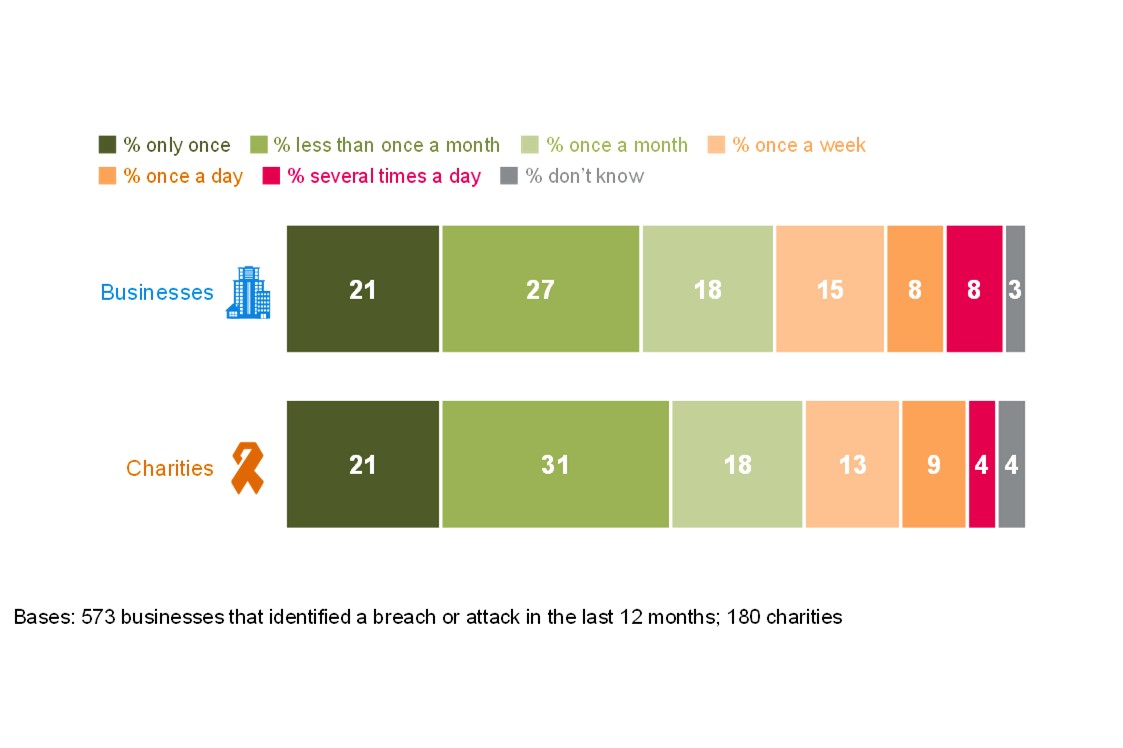

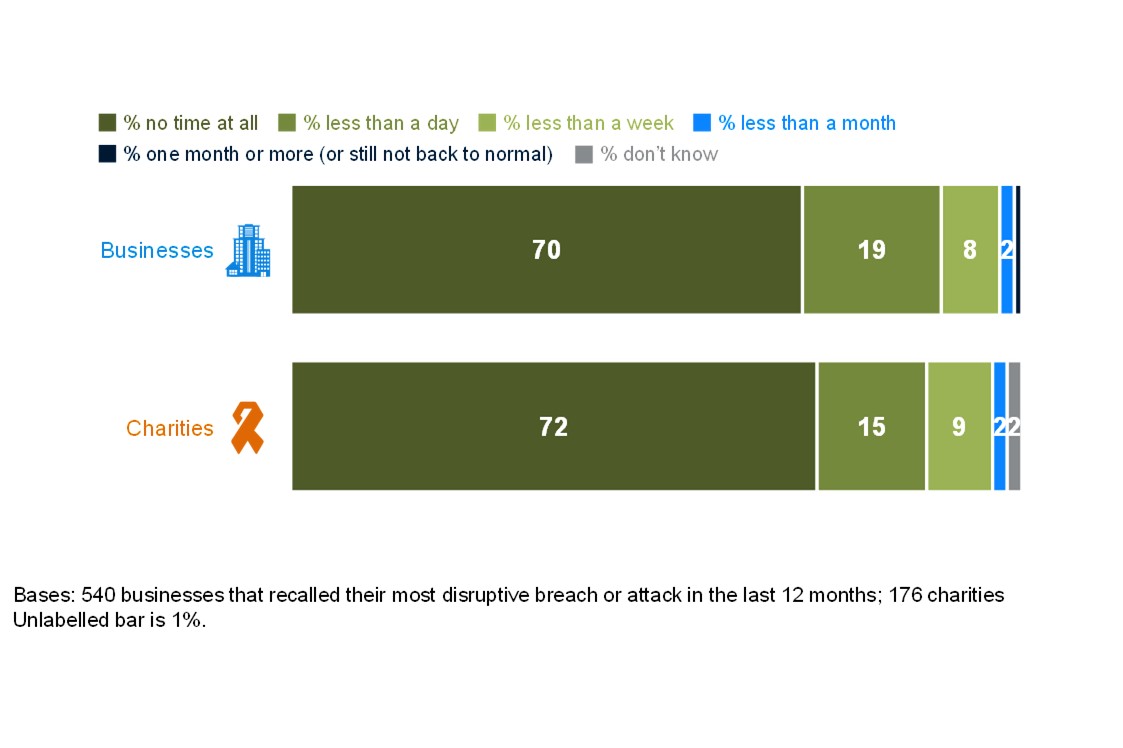

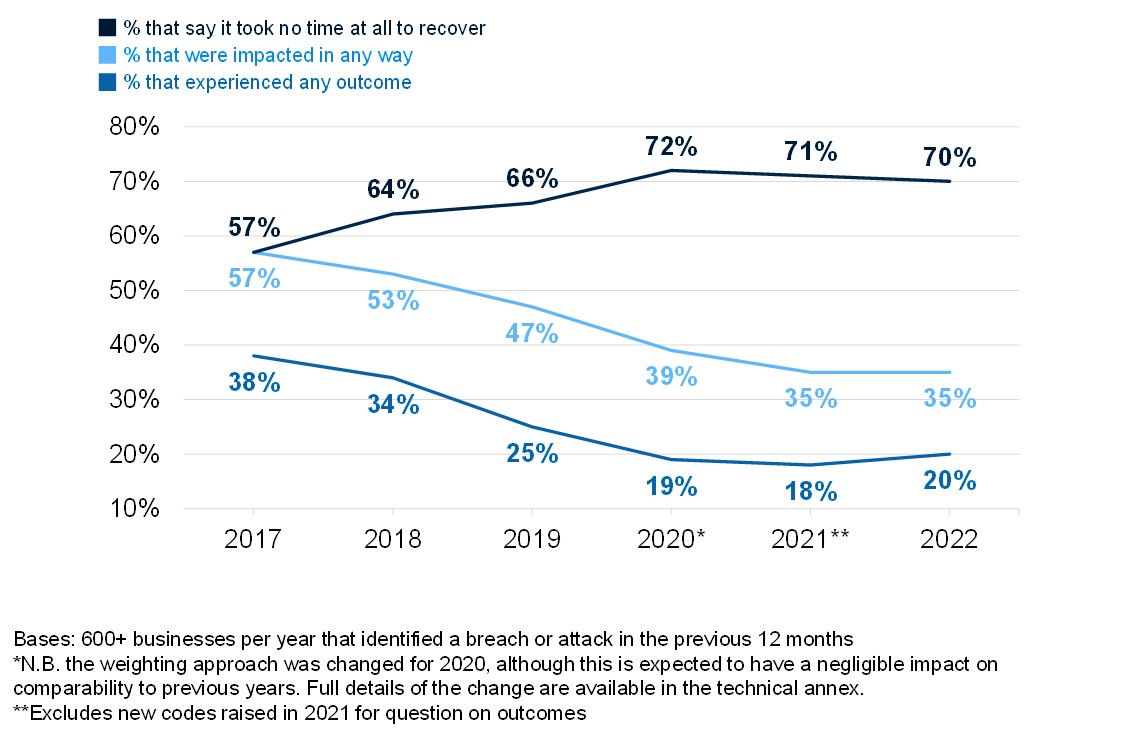

Within the group of organisations reporting cyber attacks, 31% of businesses and 26% of charities estimate they were attacked at least once a week. One in five businesses (20%) and charities (19%) say they experienced a negative outcome as a direct consequence of a cyber attack, while one third of businesses (35%) and almost four in ten charities (38%) experienced at least one negative impact.

Cost of attacks

Looking at organisations reporting a material outcome, such as loss of money or data, gives an average estimated cost of all cyber attacks in the last 12 months of £4,200. Considering only medium and large businesses; the figure rises to £19,400. We acknowledge the lack of framework for financial impacts of cyber attacks may lead to underreporting.

Cyber hygiene

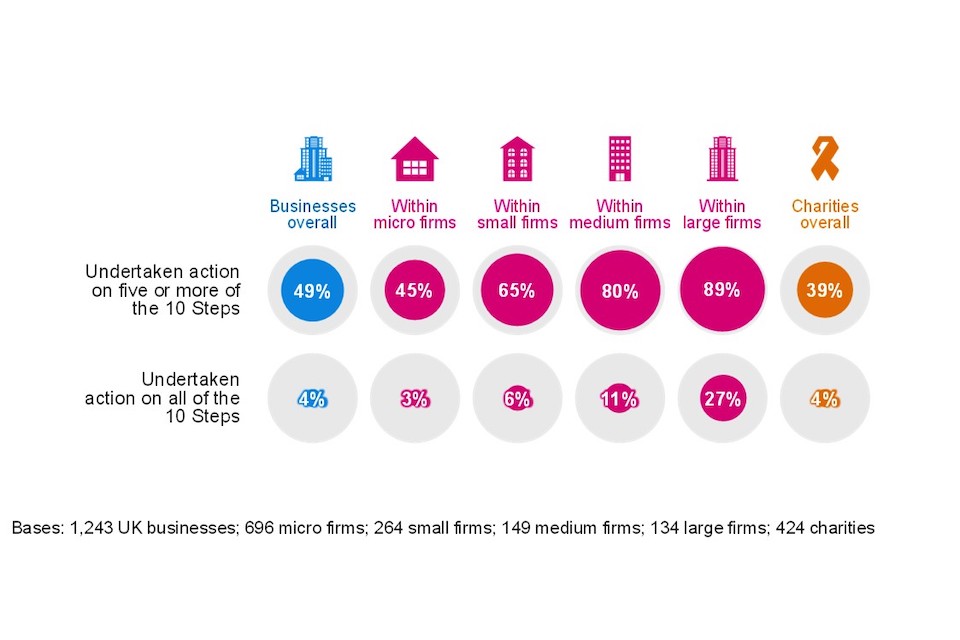

The government guidance ‘10 Steps to Cyber Security’ breaks down the task of protecting an organisation into 10 key components. The survey finds 49% of businesses and 39% of charities[footnote 11] have acted in at least five of these 10 areas. In particular, access management surveyed most favourably, while supply chain security was the least favourable.

Board engagement

Around four in five (82%) of boards or senior management within UK businesses rate cyber security as a ‘very high’ or ‘fairly high’ priority, an increase on 77% in 2021. 72% in charities rate cyber security as a ‘very high’ or ‘fairly high’ priority. Additionally, 50% of businesses and 42% of charities say they update the board on cyber security matters at least quarterly.

Size differential

Larger organisations are correlated throughout the survey with enhanced cyber security, likely as a consequence of increased funding and expertise. For large businesses’ cyber security; 80% update the board at least quarterly, 63% conducted a risk assessment, and 61% carried out staff training; compared with 50%, 33% and 17% respectively for all businesses.

Risk management

Just over half of businesses (54%) have acted in the past 12 months to identify cyber security risks, including a range of actions, where security monitoring tools (35%) were the most common. Qualitative interviews however found that limited board understanding meant the risk was often passed on to; outsourced cyber providers, insurance companies, or an internal cyber colleague.

Table 1.2: Proportion of UK businesses acting to identify cyber risks each year

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57% | 56% | 62% | 64% | 52% | 54% |

Outsourcing & supply chain

Small, medium, and large businesses outsource their IT and cyber security to an external supplier 58%, 55%, and 60% of the time respectively, with organisations citing access to greater expertise, resources, and standard for cyber security. Consequently, only 13% of businesses assessed the risks posed by their immediate suppliers, with organisations saying that cyber security was not an important factor in the procurement process.

Incident management

Incident management policy is limited with only 19% of businesses having a formal incident response plan, while 39% have assigned roles should an incident occur. In contrast, businesses show a clear reactive approach when breaches occur, with 84% of businesses saying they would inform the board, while 73% would make an assessment of the attack.

External engagement

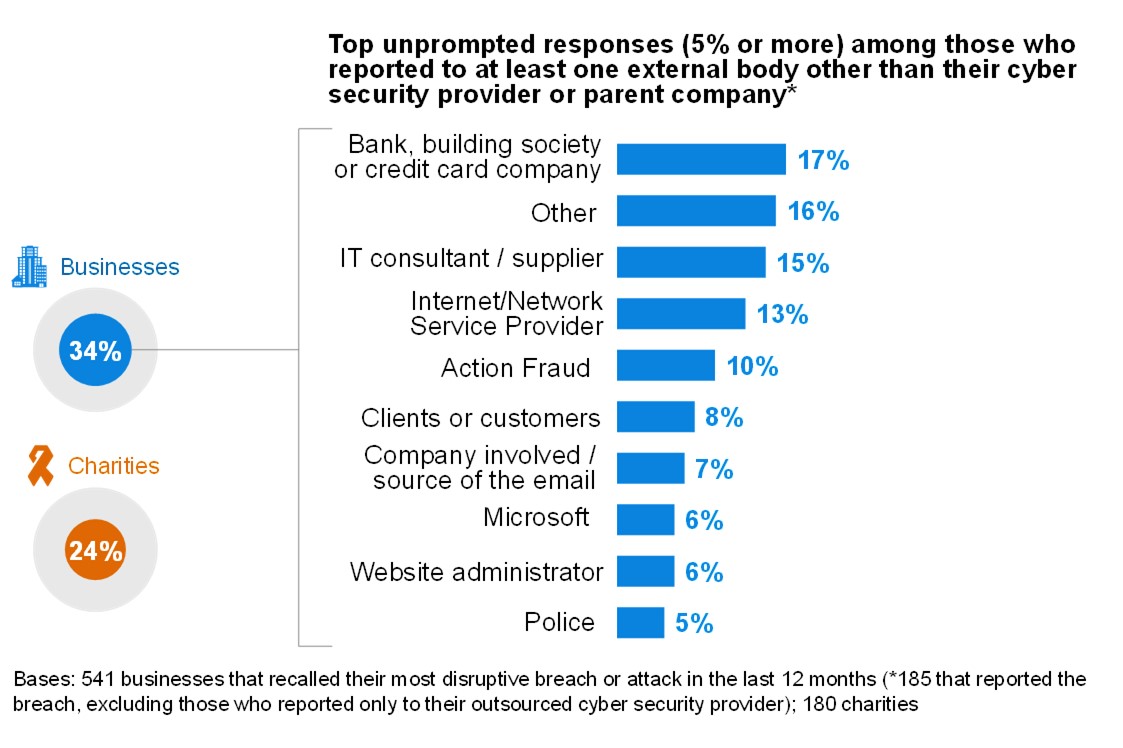

Outside of working with external cyber security providers, organisations most keenly engage with insurers, where 43% of businesses have an insurance policy that cover cyber risks. On the other hand, only 6% of businesses have the Cyber Essential certification and 1% have Cyber Essentials plus, which is largely due to relatively low awareness.

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 Code of practice for statistics

The Cyber Security Breaches Survey is an official statistic and has been produced to the standards set out in the Code of Practice for Statistics. The code is based on three pillars: trustworthiness, quality and value. To this end we have quality assured all the figures presented throughout this report to match the raw survey outputs, considered all statements to be contextually appropriate, and used a writing style to ensure it is fit for a wider audience.

1.2 Background

Publication date: 30 March 2022

Geographic coverage: United Kingdom

The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) commissioned the Cyber Security Breaches Survey of UK businesses, charities and education institutions as part of the National Cyber Security Programme. The findings of this survey provide a comprehensive description of cyber security for a representative sample of UK organisations, which provides a snapshot of cyber resilience at this current point in time. It therefore tells us what organisations are doing to stay secure, and also details the cyber threat landscape. It also supports the government to shape future policy in this area, in line with the National Cyber Strategy 2022

Survey interviews are conducted by the market research provider Ipsos UK. The project requirements and reporting are finalised by DCMS and for the 2022 publication includes:

- Cyber Security policies and processes

- Technical controls and governance for cyber security

- Board level attitudes and strategy for cyber security

- Areas of interest such as cyber security training, supply chain risk management, use of government guidance

- Cyber threat landscape, including the impacts, outcomes and estimated financial cost

- Incident response to cyber breaches

This 2022 publication follows previous surveys in this series, published annually since 2016. In each publication year, the quantitative fieldwork has taken place in the winter of the preceding year (for example, in winter 2021/22, for this latest survey). This Statistical Release focuses on the business and charity outcomes. The results for educational institutions have been included in a separate Education Annex

1.3 Methodology

As in previous years, there were two strands to the Cyber Security Breaches Survey:

- We undertook a random probability telephone survey of 1,243 UK businesses, 424 UK registered charities and 420 education institutions from 16 October 2021 to 21 January 2022. The data for businesses and charities have been weighted to be statistically representative of these two populations.

- Random Iterative Method (RIM) weighting has been applied to the survey raw data so as to ensure it is proportionate to the profile of UK organisations, with respect specifically to size and sector. All figures quoted in this report are from the weighted outputs. It should be noted that as BEIS business populations show; the composition of UK businesses is mostly micro and small, which is reflected in any overall figures in this report.

- We carried out 35 in-depth interviews between December 2021 and January 2022, to gain further qualitative insights from some of the organisations that answered the survey. Sole traders and public-sector organisations were outside the scope of the survey. In addition, businesses with no IT capacity or online presence were deemed ineligible. These exclusions are consistent with previous years, and the survey is considered comparable across years. The educational institutions, covered in the separate Education Annex, comprise 198 primary schools, 221 secondary schools, 34 further education colleges and 37 higher education institutions. More technical details and a copy of the questionnaire are available in the separately published Technical Annex.

1.4 Changes since the 2021 survey

The 2022 survey is methodologically consistent with previous years, in terms of the sampling and data collection approaches. This allows us to look at trends over time with confidence, where the same questions have been asked across years. However, this year’s study makes the following important changes:

- A small number of questionnaire changes to stay in line with DCMS policy objectives (e.g., new questions related to ransomware and managing supplier risks).

- The business sample for the 2022 publication is 12% smaller than the previous year due to homeworking practices creating significant challenges in contacting survey respondents. Any changes to the survey which result in findings no longer being comparable with previous years are flagged in the Statistical Release. These changes can be found in the Technical Annex. In particular, the changes to the cost data mean we can no longer make direct comparisons to previous years, but can still comment on whether the pattern of results is similar to previous years.

1.5 Interpretation of findings

How to interpret the quantitative data

The survey results are subject to margins of error, which vary with the size of the sample and the percentage figure concerned. For all percentage results, subgroup differences have been highlighted only where statistically significant (at the 95% level of confidence).[footnote 1] [footnote 2] This includes comparison by size, sector, and previous years. By extension, where we do not comment on differences across years, for example in line charts, this is specifically because they are not statistically significant differences. There is a further guide to statistical reliability at the end of this release.

Subgroup definitions and conventions

For businesses, analysis by size splits the population into micro businesses (1 to 9 employees), small businesses (10 to 49 employees), medium businesses (50 to 249 employees) and large businesses (250 employees or more). For charities, analysis by size is primarily considered in terms of annual income band. The sample size for charities (424) has slightly decreased this year compared to the slightly larger 2021 sample size (487). However, we have still been able to highlight income band differences, with the greatest focus being on the subgroups of high-income charities (with £500,000 or more in annual income) and charities with very high incomes (of £5 million or more).

Due to the relatively small sample sizes for certain business sectors, these have been grouped with similar sectors for more robust analysis. Business sector groupings referred to across this report, and their respective SIC 2007 sectors, are:

- administration and real estate (L and N)

- agriculture, forestry and fishing (a)

- construction (F)

- education (P)

- health, social care and social work (Q)

- entertainment, service and membership organisations (R and S)

- finance and insurance (K)

- food and hospitality (I)

- information and communications (J)

- utilities and production (including manufacturing) (B, C, D and E)

- professional, scientific and technical (M)

- retail and wholesale (including vehicle sales and repairs) (G)

- transport and storage (H).

Analysis of organisation cyber security split by geographical region is considered to be out of the scope of this reporting. While we have and may occasionally provide data specific for ITL 1 regions, we do not believe there to be substantial correlation for this cross-break. Regional differences may also be attributable to the size and sector profile of the sample in that region. Where figures in charts do not add to 100%, or to an associated net score, this is due to rounding of percentages or because the questions allow more than one response.

How to interpret the qualitative data

The qualitative survey findings offer more nuanced insights into the attitudes and behaviours of businesses and charities with regards to cyber security. The findings reported here represent common themes emerging across multiple interviews. Insights from an individual organisation are used to illustrate findings that emerged more broadly across interviews. However, as with any qualitative findings, these examples are not intended to be statistically representative.

1.6 Acknowledgements

Ipsos UK and DCMS would like to thank all the organisations and individuals who participated in the survey. We would also like to thank the organisations who endorsed the fieldwork and encouraged organisations to participate, including:

- the Association of British Insurers (ABI)

- the Charity Commission for England and Wales

- the Charity Commission for Northern Ireland

- the Confederation of British Industry (CBI)

- the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW)

- Jisc, a not-for-profit company that provides digital infrastructure, services, and guidance for UK further and higher education institutions.

- Universities and Colleges Information Systems Association (UCISA)

Chapter 2: Profiling UK businesses and charities

Organisations are more likely to suffer a breach if they increase their digital footprint, use Managed Service Providers (MSPs), or allow employees to use personal devices. This chapter covers the types of organisations that tend to be more exposed to these types of risks. It helps to contextualise some of the sector differences evidenced in later chapters.

2.1 The digital footprint of different organisations

Almost all organisations have some form of digital exposure. Over nine in ten businesses (92%) and eight in ten charities (80%) have at least one of the items listed in Figure 2.1. These are in addition to having their own websites and staff email accounts – something we have recorded as being near-universal in previous years of the survey.

Only a minority of businesses and charities take payments or bookings online. Medium (40%) and large (48%) businesses are more likely than the business average (30%) to have such payment capabilities, as are high-income charities (46% vs. 31% overall).

Network-connected devices (sometimes called smart devices) were more common amongst businesses than last year (48% vs. 46%). These can be devices such as TVs, building controls, alarms or speakers, among others. These are more commonplace in businesses than charities (48% vs. 29%). Larger organisations also report using these devices more often (66% of medium firms, 82% of large firms and 66% of high-income charities do so).

Figure 2.1: Percentage that currently have or use the following digital services or processes.[footnote 3]

| Digital service or process | Businesses | Charities |

|---|---|---|

| Online bank account | 80% | 59% |

| Personal information about customers held electronically | 61% | 61% |

| Network-connected devices^ | 48 % | 29% |

| Ability for customers to order, book or pay online | 30% | 31% |

Bases: Total: 1,243 UK businesses; 424 charities. Half A: 658 UK businesses; 185 charities ^Only asked of sample half A

We ask charities separately about two types of online activity that might affect them, over and above private sector businesses:

- Just over four-in-ten charities (44%) allow people to donate to them online.

- Around four-in-ten (42%) have beneficiaries that can access services online.

It is more common for high-income charities to allow people to donate to them online (65% of those with £500,000 or more) and to have beneficiaries that can access services online (54%) when compared to charities overall.

Sector differences

Among businesses, the sectors that are most likely to hold personal data about customers include:

- finance and insurance (85%, vs. 61% businesses overall)

- health, social work, and social care (81%)

The sectors where it is most common for customers to book or pay online are, as might be expected, the food and hospitality sector (49%, vs. 30% businesses overall) and the retail and wholesale sector (42%). The sectoral differences for finance, health, and food and hospitality industries are broadly in line with what we have found in previous years.

Food and hospitality firms are also more likely than others to use network-connected devices (59%, vs. 48% overall). The same can be said for the information communication sector (62%).

Trends over time

In 2021, businesses had adjusted their ability to deal with their finances online: more had online bank accounts (82% vs. 75% in 2020) and were able to accept online payments (30% vs 23% in 2020). This year’s results show similar results: 80% of businesses had an online bank account, and 30% of businesses accepted payments online. This suggests that businesses have either yet to recover from the impact of COVID-19, or they have adjusted to the ‘new normal’ in light of the pandemic.

2.2 Use of Managed Service Providers (MSPs)

This year, for the first time, we asked organisations whether they used a Managed Service Provider (MSP). An MSP is a supplier that delivers a portfolio of IT services to business customers via ongoing support and active administration, all of which are typically underpinned by a Service Level Agreement. An MSP may provide their own Managed Services or offer their own services in conjunction with other IT providers’ services. As shown in Figure 2.2., four in ten businesses (40%) and almost a third of charities (32%) use at least one MSP.

Figure 2.2: Percentage that use a Managed Service Provider (MSP)

Bases: 1,243 UK businesses; 696 micro firms; 264 small firms; 149 medium firms; 134 large firms; 82 finance/insurance; 424 charities

The use of MSPs was more common amongst medium-sized businesses (65%) and large businesses (72%). The use of MSPs is more common in the financial and insurance industries than businesses overall (70% vs. 40%). The financial services sector is highly regulated, offers more complex products, and poses a legitimate target for cyber attack. All of these provide a reason for firms in this sector to opt for the quality and assurance that can be provided by an MSP. High-income charities (with £500,000 or more in annual income) were also more likely to use MSPs (68% vs. 32% overall).

In the qualitative strand, we found that organisations used a variety of MSPs. Across organisations as a whole these tended to relate to cloud based services hosting emails or external data storage. Though less likely to use them, smaller organisations tended to use MSPs for services where they were unlikely to have a team of specialist staff. These included central service functions such as payroll, HR, and IT.

We then asked about the procurement processes, specifically if cyber security was considered as an important factor when selecting an MSP. Overall cyber security was not an important factor, especially amongst smaller organisations selecting MSPs for central functions. They prioritised the price of procuring the MSP as well as the overall quality of service they would offer. When selecting an email provider or data storage providers, cyber security was seen as a priority, but was not considered during procurement. Instead, they assumed that the providers would have excellent cyber security, far better than their own, owing to the fact they were often multinational technology companies.

However, organisations will often require that suppliers, including MSPs, prove they have robust cyber security when signing contracts. Once the contract is signed, though, this is not often followed up with extensive due diligence or measurement of KPIs, and risks are not reviewed throughout the duration of the relationship.

2.3 Use of personal devices

Using a personal device, such as a personal non-work laptop, to carry out work-related activities is known as bringing your own device (BYOD). Nearly half of businesses (45%) and two-thirds of charities (64%) say that staff in their organisation regularly do this, as Figure 2.3 shows.

BYOD has historically been more prevalent in charities than in businesses (since charities were first included in the 2018 survey). DCMS’s 2017 qualitative research with charities suggested that this behaviour was especially common among smaller charities. It found that they often have lower budgets for IT equipment or do not have their own office space, so have previously been more likely to encourage home working. This behaviour is also more common among entertainment, service and membership organisations.

Figure 2.3: Percentage that have any staff using personally owned devices to carry out regular work-related activities

Bases: 1,243 UK businesses; 696 micro firms; 264 small firms; 149 medium firms; 134 large firms; 146 prof/sci/technical; 424 charities

The business findings show similar results to 2021 in reported BYOD this year (45%, vs. 47% in 2021). This is counter to the long-term trend. However, this could be a reporting issue rather than a true change in the use of personal devices. For example, organisations may have less oversight of how staff working from home are accessing their files or network.

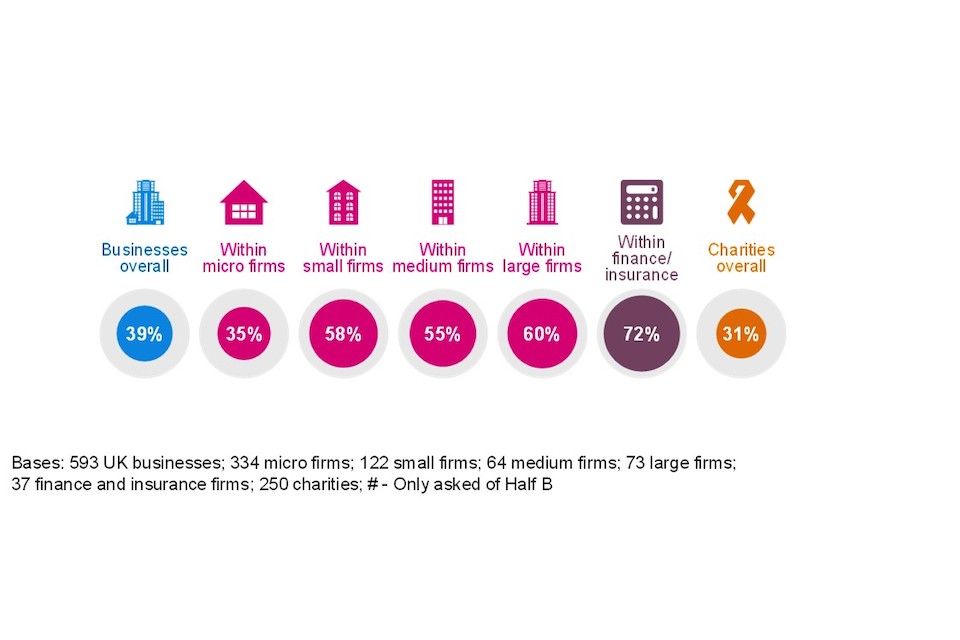

2.4 Older versions of Windows

We asked organisations if they had computers with old versions of Windows installed (i.e., Windows 7 or 8). The National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) and others have previously highlighted that some older versions (pre-Windows 8.1) have stopped being supported, so may be more vulnerable to cyber security breaches. As Figure 2.4 shows, 16% of businesses and 14% of charities say they still have older versions of Windows installed.

Figure 2.4: Percentage or organisations that have older versions of Windows installed

Bases: 593 UK businesses; 334 micro firms; 122 small firms; 64 medium firms; 73 large firms; 85 utilities/production; 250 charities; only asked of sample half B

Having older versions of Windows is more common among large businesses (23%, vs. 16% overall) and those in the utilities and production sector (26%). It is less common in the finance and insurance sector (11%), with other sectors being relatively close to the average.

Chapter 3: Awareness and attitudes

This chapter starts by exploring how much of a priority cyber security is to businesses and charities, and how this has changed over time. It also looks at where organisations get information and guidance about cyber security, how useful this is for them and what they have done in response to seeing or hearing official guidance. In the qualitative research we explore how organisations discuss and make decisions on cyber security.

3.1 Perceived importance of cyber security

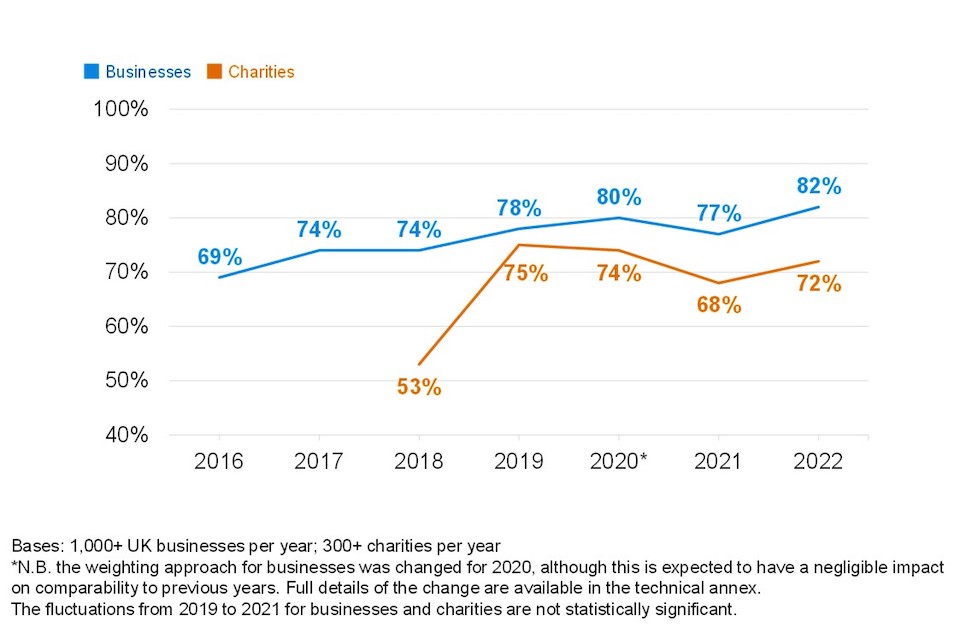

Eight in ten businesses (82%) report that cyber security is a high priority for their senior management, representing an uplift on last year (77%). Seven in ten charities (72%) say their trustees believe cyber security is a high priority. This is significantly lower than the figure for businesses and consistent with last year. As illustrated in Figure 3.1 and as found in the last survey, for both groups there is an approximately equal split between those that say it is a very or fairly high priority.

The respondent taking part in the interview is the individual at their organisation with responsibility for cyber security. In smaller organisations, this is likely to be someone in the senior management team, who can answer this question first-hand. In larger organisations, these individuals may not be senior managers, and their answers will reflect their own perceptions of their senior management teams.

Figure 3.1: Extent to which cyber security is seen as a high or low priority for directors, trustees and other senior managers

| Organisations | Very high | Fairly high | Fairly low | Very low | Don’t know | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Businesses | 37% | 44% | 13% | 4% | 1% | 82% |

| Charities | 33% | 39% | 14% | 12% | 3% | 72% |

Bases: 1,243 UK businesses, 424 charities

It is more common for larger businesses to say that cyber security is a high priority (92% of medium businesses and 95% of large businesses, vs. 82% overall, as shown in Figure 3.1). The same is true for high-income charities (92% of those with income of £500,000 or more, vs. 72% of charities overall). Almost all the very largest charities (with incomes of £5 million or more) say their trustees give cyber security a high priority (97%).

In previous years three sectors have consistently treated cyber security as a higher priority than others, and this continues to be the case. Once again, the sectors that attach the highest priority to cyber security are:

- Finance and insurance (65% say it is a very high priority, vs. 38% of all businesses);

- Health and social care (59% very high priority);

- Information and communications (58% very high priority).

While fewer than three in ten entertainment, service, and membership organisations (28%) place a very high priority on cyber security, almost seven in ten (67%) give it a fairly high priority. This combined figure of 95% puts the sector above most others. By contrast, and in line with last year, food and hospitality businesses tend to regard cyber security as a lower priority than those in other sectors (only 66% say it is a high priority, vs. 82% of businesses overall).

Trends over time

Figure 3.2 shows how the prioritisation score has changed over time and for businesses the increase since 2021 is now at an all-time high. This signifies a recovery from last year, where our qualitative research suggested that some organisations deprioritised cyber security to focus on business continuity (in light of the COVID-19 pandemic). While cyber security is now seen as a higher priority, we have not seen a corresponding increase in actions to implement enhanced cyber security.

The qualitative findings below suggest a number of challenges about how to translate board engagement with cyber security into increased cyber resilience amongst businesses. In qualitative interviews, organisations spoke of challenge around creating a clear commercial narrative that can be used in internal budget conversations, to ensure that cyber security is given appropriate investment against other competing business demands. There is a lack of understanding of what constitutes effective cyber risk management, which is compounded by a lack of expertise and perceived complexity of cyber security matters at board level.

Despite an increased figure for charities, a lower base size means this was not statistically significant. As noted in previous years, the more substantial rise for charities between 2018 and 2019 is likely to have been driven by the introduction of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in early 2018.

Figure 3.2: Percentage of organisations over time where cyber security is seen as a high priority for directors, trustees and other senior managers

3.2 Involvement of senior management

How often are senior managers updated on cyber security?

Figure 3.3 breaks down how often senior managers get updates on the state of cyber security and any actions being taken. It shows that updates tend to be more frequent in businesses than in charities, continuing a trend from previous years.

With figures that are almost identical to the last survey, half of businesses (50%) update their senior team at least quarterly, while four in ten charities (42%) also do this. Two-thirds of businesses (65%) and six in ten charities (60%) say senior managers are updated at least once a year.[footnote 4] This is in addition to those saying senior managers are updated every time a breach occurs (6% of businesses and 4% of charities). Almost a quarter (23%) of charities say they never update their senior management on actions taken around cyber security (compared to 16% of businesses).

Figure 3.3: How often directors, trustees or other senior managers are given an update on any actions taken around cyber security

| Organisations | Never | Less than once a year | Annually | Quarterly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily | Each time there is a breach | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Businesses | 16% | 7% | 15% | 15% | 15% | 10% | 10% | 6% | 6% |

| Charities | 23% | 7% | 18% | 20% | 15% | 4% | 3% | 4% | 5% |

Bases: 1,243 UK businesses; 424 charities

As in previous years, this varies greatly by the size of the organisation. Among large business, eight in ten (80%) have senior managers updated at least quarterly and within medium sized enterprises it is around seven in ten (68%). This contrasts with the situation among micro and small businesses, within which just under half (49%) provide updates at least quarterly.

Six in ten (61%) high-income charities provide quarterly updates to their trustees. A figure that rises to almost eight in ten (77%) among the very largest charitable organisations (income of at least £5 million) covered by the survey. There is wide variance by sector regarding the frequency with which senior managers are updated on cyber security actions. In three sectors at least a fifth never update their senior management. These are:

- Food and hospitality (26% never update senior managers vs. 16% of all businesses);

- Utilities, production, or manufacturing (21%);

- Retail and wholesale (20%).

In contrast fewer than one in ten within financial and insurance (4%) or information and communications businesses (9%) never update senior managers on cyber security actions. In both these sectors, around seven in ten (72%) provide cyber security updates at least quarterly (compared to 50% for all businesses).

Board responsibilities

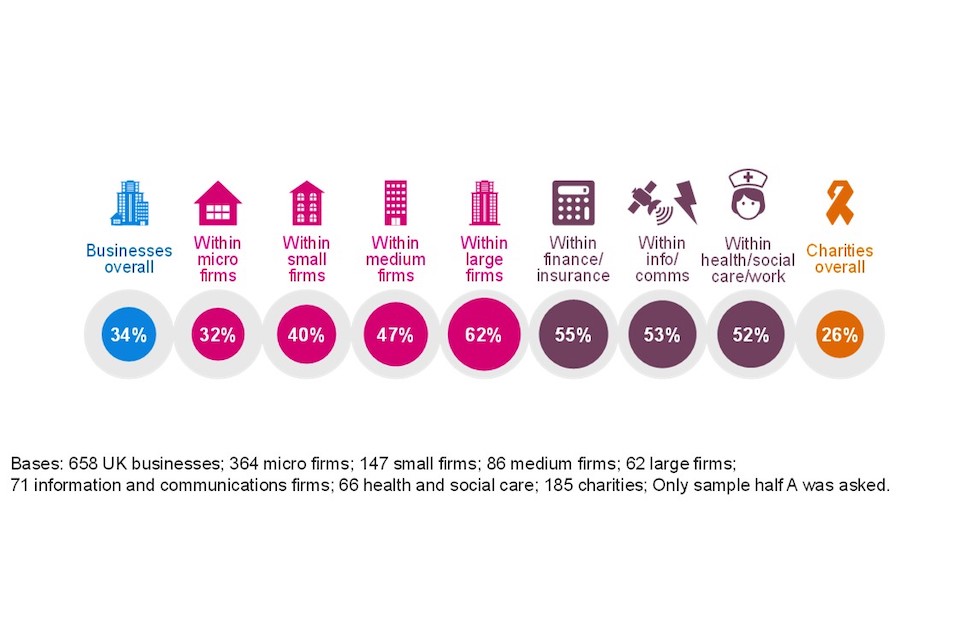

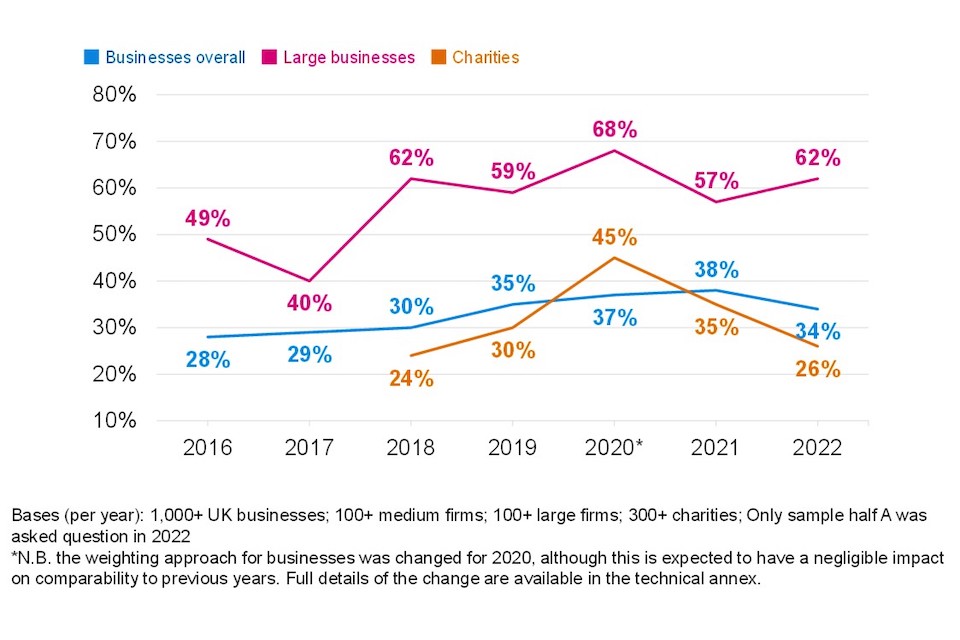

Around one third of businesses (34%) and one quarter of charities (26%) have board members or trustees accountable for cyber security as part of their job (Figure 3.4). The figure for charities represents statistically significant decline since the previous survey (35% in 2021).

As might be expected, this is much more common in larger organisations, where the management board is likely to be larger. Six in ten large enterprises (62%) have a board member responsible for cyber security.

This is not the case in charities. Across five income bands the proportion of charities reporting they have a trustee with responsibility for cyber security occupies a tight range of 25% to 29%.

Figure 3.4: Percentage of organisations with board members or trustees that have responsibility for cyber security

Finance and insurance firms (55%), information and communications firms (53%), and health and social care providers (52%) are all more likely than average to have board members taking responsibility for cyber security. The first two of these sectors were also above average in the 2021 survey. At the other end of the scale, construction firms (20%), agriculture (23%) and food and hospitality firms (25%) are among the least likely to have board members assigned this role.

Trends over time

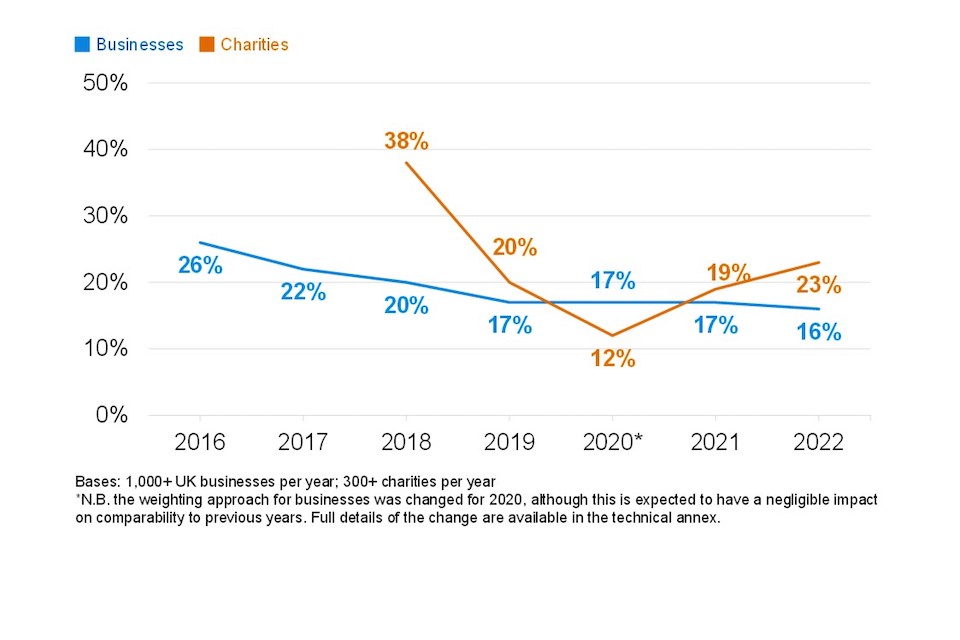

The proportion of businesses saying that senior managers have never been updated on cyber security has remained stable for the past four years (Figure 3.5). This suggests that cyber security is being discussed in boardrooms more than it was in 2016 and 2017, but despite high profile instances of cyber attacks over the last few years it is not moving any further up the agenda.

The proportion of charities saying they never update senior managers on cyber security (23%) is identical to 2021 and is close to the 2019 level. This strengthens the view expressed last year that the 2020 result could be an outlier. In the longer term, the result is more positive than the (pre-GDPR) 2018 survey. Qualitative interviews suggest that those at senior level within charities may lack the skill to address cyber security or be focused on other issues.

Figure 3.5: Percentage of organisations over time that never update senior managers on any actions taken around cyber security

Figure 3.6 shows the trend over time for board members taking on cyber security responsibilities. Among businesses this has been relatively flat over the past four years, but it remains the case that more board members are taking on cyber security roles than was the case in 2016 or 2017. For large businesses, this proportion has increased since 2021 to be in line with the 2018 and 2019 results.

Among charities, the latest result represents a significant drop since 2021 and is close to the level recorded in 2018. Qualitative research below implies that charities have decided they face greater challenges than cyber security and need to prioritise those, with fundraising revenue impacted by the pandemic. Whatever the case, the latest result suggests that the 2020 result may represent an outlier in terms of the long-term trend among charities.

Figure 3.6: Percentage of organisations over time with board members or trustees with responsibility for cyber security

3.3 Cyber security decision making

Decisions on budgeting and approaches to cyber security

A lack of board level expertise presented a significant barrier to securing the appropriate level of funding, and driving the right action in terms of an organisations overall cyber security approach. Qualitative interviews demonstrated competition for budget against other business demands. A lack of viable commercial narrative, lower perceived importance, and lack of understanding even amongst larger organisations lead to a more reactive approach as we have identified previously. The interviews found a key enabler of cyber resilience is educating the board on key threats as well as prudent cyber risk management. Often organisations are dependent on a staff member with expertise to effectively communicate this to board level.

There tended to be an awareness and acknowledgement of cyber risks at a high level. However, boards tend to trust and defer the finer details of a cyber security approach to their IT teams (in the case of larger organisations) or third parties and external providers (in the case of smaller organisations). This is because there was a low level of knowledge of the technical details of cyber risks and how to manage them at senior management and board level. There was a lack of serious understanding of the risks outside of specialist staff within organisations. However, those with specialist staff within the company or a network of specialist advisers or third parties were better able to make decisions favouring cyber security.

“We take our lead from IT. They would bring to our attention something and say if your system isn’t at this level, there’s a good chance you could get hacked so we really leave them to make sure that we are as protected as possible. If they said to us, you could have this all singing all dancing set up, but it would cost you 10 grand, you’d probably say no thanks… they’d have to make a business case.” Large charity

Larger organisations often had a more layered approach to decision making:

- In larger organisations, the cyber security budget would often be part of a wider IT budget. Senior IT or cyber security staff would present their plans to board. Boards would often trust their judgement on technical details on suggested approaches to cyber security, but there were often challenges around making the business case for change. This meant they were competing with other departments for money, and it was up to the boards to decide how much investment cyber security should have. Often this led to more immediate or tangible risks (such as physical security of premises) being prioritised over cyber security.

- In some larger organisations there were cyber security experts in senior roles. This made it easier for organisations to make the business case for increased cyber security spending. In turn, this allowed them to have a cyber security sponsor on the board who could champion more complex controls, such as threat intelligence or penetration testing. A senior leader with good understanding of cyber security improved the knowledge of other board members. This increased awareness amongst the wider body of staff.

“They are very much involved in the top-level budget, and if it’s anything above a threshold, and it’s not a defined threshold of 500 pounds or 5000 if it’s something that I deem that actually the board should be aware of, they need to make a decision that is strategic. I’ll brief them, and they’ll make a decision. Generally, the day to day running [of cyber security] is left to myself.”

Large business

In smaller organisations there was a low level of internal cyber security expertise. Often this meant that decisions relating to cyber security were made as part of wider initiatives. For instance, a small charity stated that they ensured their data was stored on a cloud provider and encrypted. However, they also stated this was driven by a desire to protect sensitive data and comply with GDPR regulations as opposed to ensuring the organisation had robust cyber security. This meant that they did not have fixed cyber security budgets. Instead, investment was secured if improving cyber security was deemed as important to the future direction of the organisation or mitigated potential risks.

Challenges on cyber security decision making

Despite high prioritisation shown in figures 3.1 and 3.2 there are many factors across organisations that make decision making challenging and inhibit a good cyber security approach. This may help explain why many metrics by which we measure cyber resilience in Chapter 4 have either flatlined or declined over the past two years.

Ultimately, and as mentioned previously, there was a lack of knowledge of cyber security at a senior level. Even for exceptions where organisations had senior leaders with cyber expertise, this tended to be accidental, and their core role did not explicitly relate to cyber security. Therefore, there was a consistent challenge to convince management of the seriousness and strategic threat cyber attacks posed. Senior leaders tended to be focused on day-to-day priorities instead, with this being exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

There were also challenges that were specific to certain types of organisations. Typically, in larger organisations:

- The lack of expertise on board sometimes fostered a lack of curiosity in cyber security policy. This led to more reactionary measures (e.g., boosting security to comply with GDPR) as opposed to taking a pro-active stance on cyber security. However, that is not to say they did not trust their IT staff with cyber security.

- The high level of trust in cyber security staff amongst boards can sometimes present a challenge. It is often on IT or cyber security staff to make a good case for cyber security risks being present and investment to mitigate them. This was often not in their core skillset, meaning important risks were deprioritised and budget went elsewhere. Therefore, it was critical that boards balanced the trust they had in their IT staff with their own ability to judge a business case on its technical merits.

Smaller organisations took little proactive action on cyber security, driven by a lack of internal knowledge and competing priorities with their budgets. This was especially the case if they had no relationships with outsourced cyber security providers or IT specialist MSPs. They often had a fear of the technicalities of cyber security and a preference to not research and mitigate against the risks they presented. They knew there could be a potentially devastating impact, but were not sure of the specifics of this, and felt it was low probability. This meant budget priorities often focused on the immediate operational side of the organisation.

“I think it’s just been something that we’ve known the word cybersecurity, but never thought given the scale and size of our business, that it’s something that we need to worry about. It’s something that banks and government departments need to be concerned about in terms of data breaches. It’s not something that is his concern for us.” Small business

Though this challenge did affect all organisations, there was a particular issue with charities on a lack of focus or aim when it came to cyber security. A lack of new regulations to enforce meant that charities felt there was no immediate need to prioritise cyber security in a way they had done when GDPR became law.

In order to overcome these challenges IT teams had to engage boards through how they framed cyber security. Boards were more receptive if they viewed cyber security as a threat to business continuity carrying an operational or financial risk. This allowed them to visualise the impact a serious breach could have and made facilitating discussion and, ultimately, securing the desired budget more straightforward. Conversely, board members were less likely to engage if it was presented solely as an IT issue. Some organisations, particularly smaller charities, had started to attempt to overcome the challenges and their own lack of expertise in this area by joining networks of CEOs or other organisation leaders to tackle cyber security.

“[Training and briefing board] was to frame their understanding of the risk of the impact of non-compliance… If they understand the risk and the impact of the business and then as directors, it will frame them in making decisions. And it was worthwhile because they don’t challenge me, but they understand why I’m saying that. We need to update all of our Windows because when new ones coming in, if it’s not patched and it’s not updated. It’s going to cost the business.” Large business

3.4 Sources of information

Overall proportion seeking cyber security information or guidance

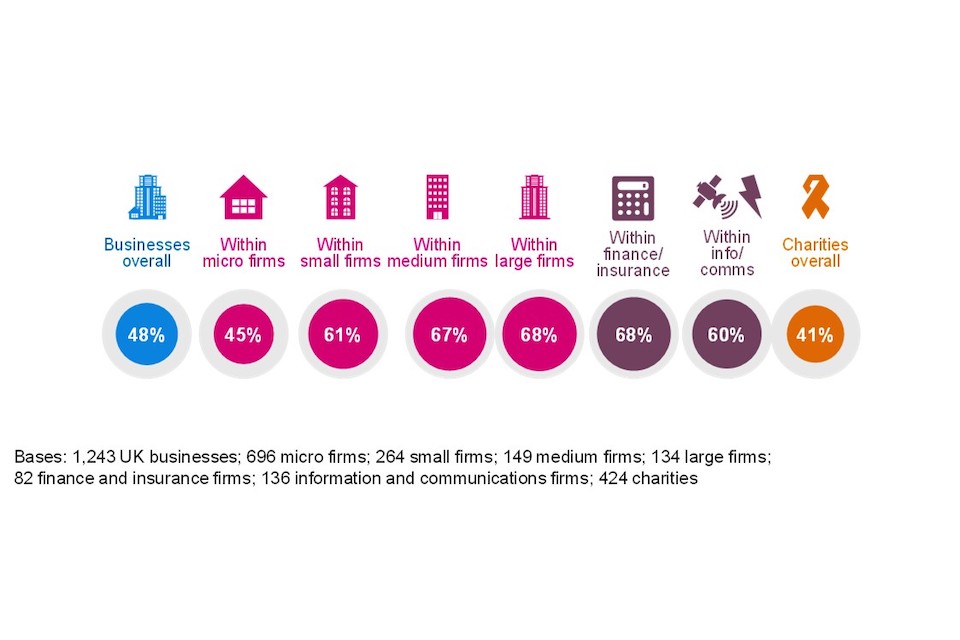

We ask organisations where they seek information, advice, or guidance on the cyber security threats they face. It is then determined whether the sources sit within their organisation or are an external source. External sources include government sources, third party cyber security or IT providers, trade bodies, or general sources such as an internet search or from the media. Around half of businesses (48%) and approximately four in ten charities (41%) report actively seeking information or guidance on cyber security from outside their organisation in the past year.

As Figure 3.7 illustrates, external information is more often sought by small, medium, and large businesses, rather than micro firms where a minority has taken such action. The sectors where firms are most likely to seek out external information are finance and insurance (68%), information and communications (60%) and professional, scientific, and technical (60%).

Larger charities seek external information to a much greater degree than their smaller counterparts. Seven in ten charities with an income of £500k or more (72%) sought external information compared to under four in ten charities with an income of less than £100k (37%).

For businesses overall, this result is lower than in 2021 (53%). It is similar to the peak observed in 2018 and 2019 (59%), following the implementation of GDPR. For large businesses specifically, the figure of 68% is also lower than last year (75%) but remains above 2020 (57%) and 2019 (64%). This may indicate that the volume of large businesses seeking information during the COVID-19 pandemic is now subsiding.

For charities (41%), the latest result is in line with that seen over the course of the past few years, where the figure seeking external information has typically been around half or just under.

Figure 3.7: Proportion of organisations that have sought external information or guidance in the last 12 months on the cyber security threats faced by their organisation

As in 2021 a small minority of businesses and charities seek information internally within their organisations (3% of businesses and 7% of charities).

Where do organisations get information and guidance?

As in previous years, the most common individual sources of information and guidance are:

- external cyber security consultants, IT consultants or IT service providers (mentioned by 25% of all businesses and 18% of all charities);

- general online searching (8% of businesses and 5% of charities);

- any government or public sector source, including government websites, regulators, and other public bodies (8% of businesses and 10% of charities).

These have also been the most frequently mentioned sources in previous years. The huge range and diversity of individual sources mentioned, together with the relatively low proportions for each, highlights that there is still no commonly agreed information source when it comes to cyber security. For example, just one per cent of both businesses and charities overall mention the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) by name. Among charities, fewer than one in ten (7%) mention charity-specific sources such as their relevant Charity Commission.[footnote 5]

Awareness of government guidance, initiatives and communications

The unprompted question around information sources tends to underrepresent actual awareness of government communications on cyber security, as during a live interview people cannot always recall specific things they have seen and heard, often a relatively long time ago. We therefore asked organisations whether they have heard of specific initiatives or communications campaigns before. These include:

- The national Cyber Aware communications campaign, which offers tips and advice to protect individuals and organisations against cybercrime;

- the 10 Steps to Cyber Security guidance, which aims to summarise what organisations should do to protect themselves;

- the government-endorsed Cyber Essentials scheme, which enables organisations to be certified independently for having met a good-practice standard in cyber security.

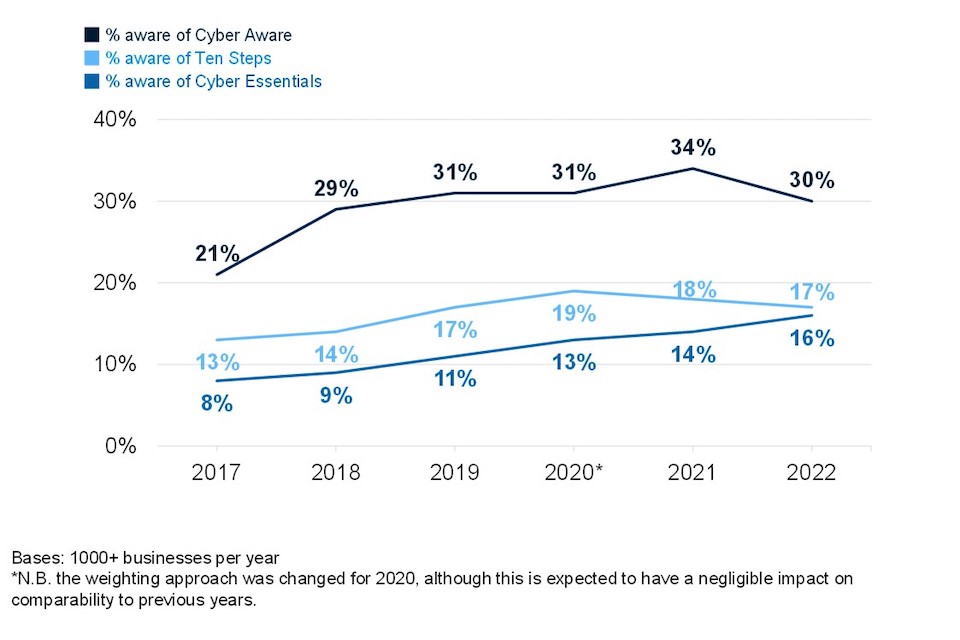

Figure 3.8 illustrates that awareness of these schemes and initiatives is broadly unchanged from the previous survey. More have heard of Cyber Aware than the other schemes, but still only a minority of businesses and charities are aware of each one.

Figure 3.8: Percentage of organisations aware of the following government guidance, initiatives or communication campaigns

| Government guidance | Businesses | Charities |

|---|---|---|

| Cyber Aware campaign | 30% | 38% |

| The Cyber Security Board Toolkit | 17% | 11% |

| 10 Steps guidance | 17% | 20% |

| Cyber Essentials scheme | 16% | 19% |

| Any Small Business Guides, such as the Small Business Guide to Cyber Security | 16% | 18% |

Bases: 1,243 UK businesses; 424 charities

Firms operating within the professional, scientific, and technical; financial and insurance; and information and communications sectors, tend to be more aware of these schemes or campaigns. Medium and large firms are also substantially more aware of these guidance packages, as are the larger charities, as shown below:

- Cyber Aware:

- 51% of medium firms and 49% of large firms

- 38% in both professional, scientific, and technical, and financial and insurance

- 47% of charities with £500k plus income, 62% in £5 million plus

- 10 Steps guidance:

- 34% of medium firms and 38% of large firms

- 26% in financial and insurance, 24% in information and communications

- 34% of charities with £500k plus income, 53% in £5 million plus

- Cyber Essentials:

- 49% of medium firms and 62% of large firms

- 36% in information and communications, 28% in both professional, scientific, and technical, and financial and insurance

- 43% of charities with £500k plus income, 76% in £5 million plus

There tends to be little difference between UK regions when it comes to attitudes and awareness towards cyber security. Therefore, it is noteworthy that in Scotland awareness of both Cyber Aware (43%) and 10 Steps guidance (25%) is higher than businesses elsewhere.

As Figure 3.9 shows, awareness of Cyber Essentials continues to gradually increase year on year. However, awareness of Cyber Aware and Ten Steps has remained at the same level for three consecutive years.

Figure 3.9: Awareness of government initiatives amongst businesses

Although it still amounts to no more than a fifth of charities, among these organisations’ awareness of Cyber Essentials (19%) has increased significantly since 2021 (10%). However, awareness of Cyber Aware and Ten Steps is unchanged from last year and remains eight percentages points higher than in 2018 (when charities were first included in the survey).

Guidance targeted at specific types of organisations

We also asked again this year about NCSC guidance that is directed to specific sizes of business or towards charities. This includes:

- The NCSC’s Small Business Guide and Small Charity Guide, which outline more basic steps that these smaller organisations can take steps to protect themselves; and

- The NCSC’s Board Toolkit, which helps management boards to understand their obligations and to discuss cyber security with the technical experts in their organisation. For these sets of guidance, we find that:

- 16% of micro and small firms have heard of the Small Business Guide (unchanged from 18% in 2021)

- 18% of charities have heard of the Small Charities Guide (consistent with 2021)

- 14% of medium businesses have heard of the Board Toolkit (down from 18% in 2021, but still up from 11% in 2020)

- 27% of large businesses have heard of the Board Toolkit (compared to 24% in 2021).

Impact of government information and guidance

As outlined above in Figure 3.8, just under half of businesses (45%) and over half of charities (54%) have seen at least one of the initiatives or communications campaigns covered by the survey. As we did in 2021, this year we asked those that recalled seeing any of the government communications or guidance covered in the previous section an unprompted follow-up question. This explored whether exposure to the initiatives has led to them making changes to their cyber security.

In total, over four in ten businesses (44%) and charities (49%) report making changes to their cyber security measures as a direct response to seeing this government guidance. Both figures represent an increase since 2021 (37% and 38% respectively), suggesting that while ‘exposure’ may not have increased, organisations are now more motivated to act upon the guidance they see.

Across businesses, there is some variation by size. Micro businesses are notably less likely to have taken action as a result of hearing or seeing campaigns or guidance (41%), than those in small (56%) and large businesses (52%).

Among charities, two-thirds (66%) of those with an income of £500k or more that have seen relevant communications, also say they have made changes in response. The same figure is reported by charities with £5 million or more and is higher than the charity sector average of 49%.

In terms of the specific changes made, there are a wide variety of responses given, and no single response appears especially frequently. Only “changing or updating firewalls or system configuration” (10% of business and 9% of charities) and “changed or updated antivirus or antimalware software” (8% and 10%) were mentioned by approaching one in ten. Grouping specific comments into broad categories the following picture emerges:

- 25% of all businesses and 29% of all charities aware of campaigns and initiatives report making changes of a technical nature (e.g., to firewalls, malware protections, user access or monitoring). The figure for charities is a significant increase on last year (17%).

- Similar to 2021, 13% of businesses and 15% of charities say they have made changes to do with staffing (e.g., employing new cyber security staff), outsourcing or training. The third most common single response is to say they have implemented new staff training or communications (7% of businesses and 9% of charities).

- Also similar to last year, 15% of businesses and 16% of charities have made governance changes in response to seeing or hearing official guidance on cyber security.

Seeking and understanding information and guidance

In the qualitative interviews, we asked organisations about where they seek information or guidance on cyber security. Organisations had a range of different sources, such as providers of a cloud service, the government and information on the internet. Some organisations typically sought out information for a particular cyber security problem, which could be in response to an issue they had faced, or because of media reports about a specific cyber security problem. Some other organisations undertook a general search for information.

In larger organisations, information seeking tended to be proactive, and a constant part of their cyber security processes. Many of those interviewed described constant information seeking on cyber threats as part of their job role. Some large organisations used cyber security information forums (such as Jisc CISO, which focuses on threats to universities, and an energy-sector task group) to get the most up-to-date information on threats and some used the NCSC to find information about cyber threats, which provides good and up-to-date information. Organisations would also often seek out information in relation to a particular media story. Some would go on cyber security message boards, such as Darktrace, for the most up-to-date information on these. Some organisations believed that the government was not a useful source for information on current threats, due to how slow they can be in updating organisations on current threats.

Smaller organisations tended to seek out information on a reactive basis. This could be in response to a story in the media or a specific problem they were trying to address. Smaller organisations had a variety of sources they might call on, from specific experts on cyber security to general searches on the internet. The difference in information seeking between smaller and larger organisations is likely due to the extra capacity that larger organisations have; many have specific cyber security or IT teams to do this work for them. Competing priorities in day-to-day operations also impact the ability to seek out information on cyber security. In smaller organisations, there are many competing priorities which make regular information seeking difficult. Understanding of cyber security issues also impacted an organisation’s ability to seek out information and guidance. Some organisations found cyber security guidance overwhelming, due to the high level of knowledge they believed they would need to understand it.

Chapter 4: Approaches to cyber security

This chapter looks at the various ways in which organisations are dealing with cyber security. This covers topics such as:

- risk management (including supplier risks)

- reporting cyber risks

- cyber insurance

- technical controls

- training and awareness raising

- staffing and outsourcing

- governance approaches and policies.

We then cover the extent to which organisations are meeting the requirements set out in government-endorsed Cyber Essentials scheme and the government’s 10 Steps to Cyber Security guidance .

4.1 Identifying, managing, and minimising cyber risks

Actions taken to identify risks

The survey covers a range of actions that organisations can take to identify cyber security risks, including monitoring, risk assessment, audits, and testing. Organisations are not necessarily expected to be doing all of these things – the appropriate level of action depends on their own risk profiles.

Figure 4.1 shows the six actions covered by the survey. The most common actions remain deploying security monitoring tools and undertaking risk assessments. By contrast, penetration testing and threat intelligence are undertaken mostly by larger businesses suggesting smaller businesses may not have the funding to do this. These results are similar to those observed in 2021. Additionally, the ‘decline’ in security monitoring seen in 2020 (down from 40% to 35%), has not recovered. This could be because businesses continue to struggle to monitor multiple endpoints as remote working continues, where last year’s qualitative interviews highlighted this as a key issue.

Figure 4.1: Percentage of organisations that have carried out the following activities to identify cyber security risks in the last 12 months

| Activities | Businesses | Charities |

|---|---|---|

| Any of the listed activities | 54% | 41% |

| Used specific tools designed for security monitoring | 35% | 27% |

| Risk assessment covering cyber security risks | 33% | 26% |

| Tested staff (e.g. with mock phishing exercises) | 19% | 15% |

| Carried out a cyber security vulnerability audit | 17% | 14% |

| Penetration testing | 14% | 9% |

| Invested in threat intelligence^ | 14% | 10% |

Bases: 1,243 UK businesses; 424 charities; ^only asked half A, 658 UK businesses; 185 charities

As has been established in previous years, each of these actions are more common in medium and large businesses, as well as high-income charities (with £500,000 or more).

Looking at large businesses, at least half have taken each action. Investment in threat intelligence has the lowest take up at 52%. The figure rises to 67% for using specific tools such as intrusion detection systems. Among charities with an income of £5 million or more, cyber security risk assessment (67%) is the action taken most often. Although higher than their smaller counterparts, only a third (31%) of very high-income charities invest in threat intelligence.

Information and communications firms (74%) and finance and insurance firms (69%) continue to be more likely than the average business (54%) to have taken any of these actions. At the other end of the spectrum, construction firms (41%) and those in the food and hospitality sector (42%) are less likely to have done any of these things. This sectoral pattern is similar to previous years.

Qualitative insights on threat intelligence

This year we asked organisations about their awareness and use of threat intelligence, and whether the board had knowledge of threat intelligence. Some organisations viewed threat intelligence as a useful tool for keeping themselves aware of current problems. However, in other organisations there was a lack of awareness about what threat intelligence was, particularly in organisations which did not have a specific IT or cyber security team.

Some large organisations had threat intelligence from multiple sources, mostly external sources, including the NCSC and from clients and partners. Some organisations were part of intelligence-sharing portals which gave them information on current cyber threats. There was also third-party involvement, with some receiving intelligence on public vulnerabilities and foreign threats. This was seen to give them improved detection capabilities, as it would be difficult to acquire this kind of information in-house, due to competing priorities within an organisation. Organisations also used internal tools for threat intelligence: one organisation had an internal global cyber defence centre that managed threat intelligence for the firm. Some organisations chose not to purchase threat intelligence due to the cost, and used internal resources instead.

In smaller organisations, there was a lot of variation in the level of awareness of threat intelligence and some had no knowledge of what threat intelligence was. The threat intelligence received tended to be quite simple: for example, a payment provider making them aware of a current cyber threat, rather than information from a firm dedicated to threat intelligence.

“It might have been because we use software to constantly scan, update the system. But we don’t have cyber threat intelligence.” Small charity

How organisations undertake audits and implement their findings

Among the 17% of firms that undertake cyber vulnerability audits, similar proportions undertake internal audits (35% of businesses) or external audits (39%). One in five (21%) carry out both. The proportion conducting both internal and external audits has fallen eight percentage points since 2021; with those solely using external audits increasing (39% vs. 32% in 2021).

How businesses undertake audits is strongly linked to the size of the organisation:

- Micro businesses are most likely to solely use internal staff to undertake audits (39% of the micro firms undergoing any type of audit);

- Micro and small businesses have the greatest tendency to only use external contractors (39% and 42% respectively);

- Large businesses, likely having greater financial and personnel capacity, are most likely to state that audits have been undertaken both internally and externally (56%).

Fourteen per cent of charities have carried out cyber security vulnerability audits. Due to the lower overall sample size for such charities (effective base size of 41), this limits the ability to analyse the type of audit undertaken. Charities’ cyber security vulnerability audits are equally split between those conducted internally (33%), externally (30%) or by both parties (36%), but caution must be applied due to low base sizes.

Reviewing supplier risks

Suppliers can pose various risks to an organisation’s cyber security, for example in terms of:

- Third-party access to an organisation’s systems;

- suppliers storing the personal data or intellectual property of a client organisation;

- phishing attacks, viruses or other malware originating from suppliers.

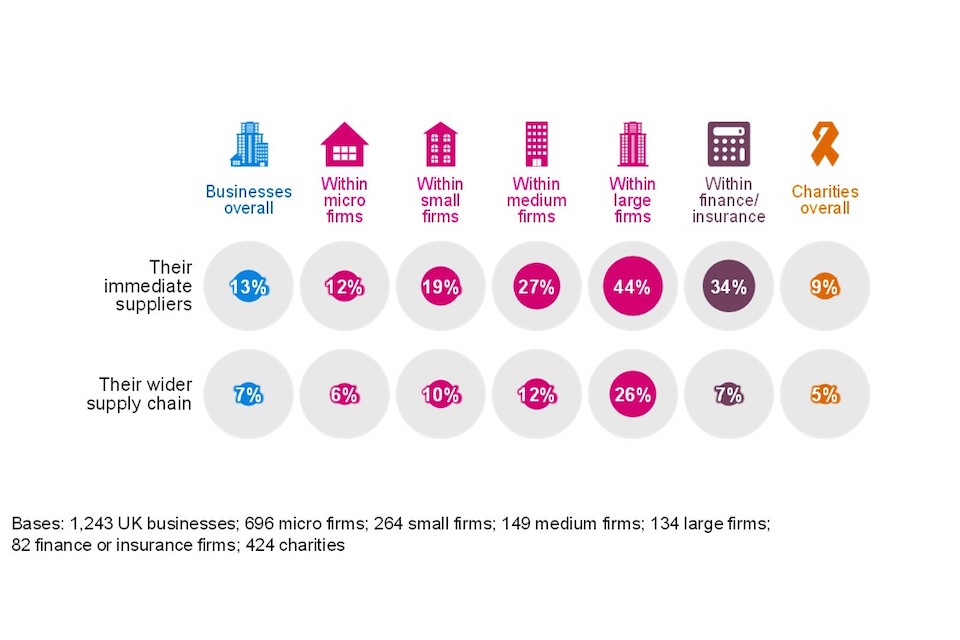

While they undoubtedly exist, relatively few businesses or charities are taking steps to formally review the risks posed by their immediate suppliers and wider supply chain. As Figure 4.2 shows, just over one in ten businesses review the risks posed by their immediate suppliers (13%) and the proportion for the wider supply chain is half that figure (7%). Among charities the respective figures are even lower (9% and 5%).

The overall figures mask a wide variation by size of organisation. Possibly reflecting a more complex supply chain, nearly three in ten medium (27%) and over four in ten large businesses (44%) review the cyber security risks posed by their immediate suppliers. The respective figures for reviewing their wider supply chain are 12% and 26%.

Among charities with very high incomes, half (50%) have reviewed the risks posed by their immediate suppliers or partners and three in ten (29%) report looking at wider supply chain risks. The figures for reviewing supply chain risks represents a significant increase on last year, where the figure was 9%.

Reflecting a generally more sophisticated approach to cyber security overall, businesses in the finance and insurance (34%), and information and communications (28%) sectors are more likely than average (13%) to monitor the risks posed by their immediate suppliers. However, this year there are no significant sectoral differences as regards reviewing wider supply chains. Excluding transport and storage where the sample size is too small for reliable analysis, fewer than one in ten firms in any sector review the potential cyber security risks in their wider supply chain.

Figure 4.2: Percentage of organisations that have carried out work to formally review the potential cyber security risks presented by the following groups of suppliers

These results are broadly in line with the 2021 figures. It is worth noting though, following last year’s small but significant drop (9% in 2020 vs. 5% in 2021), the proportion of businesses saying they have reviewed wider supply chain risks (7%) now lies between that recorded in 2020 and 2021. Among large firms the figures for both immediate suppliers (44% vs. 36%) and the wider supply chain (26% vs. 20%), are higher this year than in 2021.

How and why organisations monitor supply chains

In the qualitative interviews, we talked to organisations about how they monitor their supply chain and how often they spoke with their suppliers about cyber security. Organisations did not see their supply chain as a serious risk, but some had consistent contact with suppliers. Some firms admitted that there tended to be some complacency at board-level when considering supplier risks.

There was a lot of variation in how organisations perceived their supplier risk. There tended to be some complacency around cloud-based suppliers: many organisations believed that these could not pose a threat to their own security. This was particularly apparent when discussing the cyber defences of ‘big tech’ companies, where organisations commonly perceived them to be invulnerable to cyber attacks.

“We’re now leveraging more client services; we have more suppliers hosting client services for us. Our own data centre footprint is drastically shrinking. We’re relying on suppliers to do more work on our behalf.” Large business

There was variation in the process of taking on a new supplier: some organisations had a formal process, perhaps with board-level involvement, whereas others (often smaller organisations) had no formal process. Some organisations took their supply-chain risk very seriously, and only dealt with suppliers on a one-to-one basis and would demand to see IT protocols. There was a belief amongst some organisations that supply-chain risk had increased in the past few years. Some organisations felt that the prominence of ransomware attacks in the media had caused them to think more about risks within their supply chains, despite the fact these two issues are not always related.

There was also variation amongst organisations in terms of how much contact they had with their suppliers. Of those who had contact with their suppliers, organisations said it was usually on an annual basis to discuss terms of a contract, but a small number of organisations kept up regular contact with suppliers, talking to them multiple times a week about concerns. There were also organisations who had never had contact with a supplier, once again citing their belief in the safety of big tech firms.

“I suppose I think I’m aware that the dialogues across the technical level regarding security patches are part of that ongoing dialogue, but it’s not kind of let’s sit down and talk about cybersecurity. One hopes that we’re using suppliers that are over the level of surety that that is just part and parcel of what they do. I think we’ve been very nervous about handing over access to a small one proven player.” Large business

Some small organisations felt their size prohibited them from reacting to risks from suppliers. For some organisations, the specific service a supplier provided meant they could not look elsewhere, even in the event of the supplier’s system being compromised.

Barriers to addressing supplier risks

Businesses that review supplier risks see the key barriers to addressing them as a perceived lack of time or money (36%). This is mentioned twice as often as not knowing which suppliers to check (18%), or a lack of relevant skills (18%). Almost one in three businesses (28%) cite a lack of information from suppliers as something that inhibits their ability to manage cyber security threats. The rank order and magnitude of each barrier is broadly consistent with last year’s survey.

Overall, nearly a third of businesses (32%) say none of the six factors prevent them from understanding potential cyber security risks within their supply chain. In 2021, the corresponding figure was 36%.

Figure 4.3: Barriers to businesses undertaking formal review of supplier or supply chain risks

Base: 269 UK businesses that have formally reviewed supply chain risks

As fewer than one in ten charities have reviewed supply chain risks, caution must be exercised due to the low base size. A perceived lack of time or money (46%) is the main difficulty charities face when seeking to understanding their supply chain cyber security risks. A third (33%) report that not knowing which checks to make is a limiting factor, but only 14% said a lack of prioritisation was limiting their work in this area.

Corporate reporting of cyber security risks

This year we asked organisations how cyber security is discussed in any publicly available annual reports. Very few businesses make annual reports publicly available and where they do, they tend not to cover the cyber security risks faced by their organisation. One in ten businesses (11%) published an annual report in the past 12 months, and among these the same proportion (11%) covered cyber security within it. Even across all sectors, no more than 15% of businesses publish an annual report.

Annual reports are more common amongst larger businesses, due to the range of stakeholders who must be involved, as well as the complexity of reporting on cyber security. Larger organisations are more likely to have the necessary resources for these. Four in ten (40%) large businesses published an annual report in the past 12 months. This compares to 25% of medium sized firms and 10% of micro/ small businesses. Within these reports, large businesses (30%) are significantly more likely than medium (16%) or micro/small (10%) businesses to publicly report on the cyber security risks they might face.

For many charities it is a statutory obligation to publish annual reports and with that, they are five times more likely than businesses to have done so within the past 12 months (54% vs. 11%). For charities with an income of £100,000 and above, the figure is at least 60%. However, fewer than one in twenty charities (4%) that have published an annual report in the past 12 months covered cyber security risks within it. The figure does rise to 14% in the very largest charities with incomes of £5 million or more.

In the qualitative interviews we asked organisations that mention cyber security in corporate reporting what this involved. Cyber security tended to be acknowledged as a risk, but the specifics were not assessed in any great detail. This was because cyber security was considered amongst a wider set of risks, meaning there was limited scope to go into detail. There was also little appetite to go into detail on the technical aspects of cyber risks. This was because the reports were often signed off by boards and written by staff from outside of IT departments, meaning that there was a limited understanding of the technicalities. There were reputational and security concerns about being too descriptive with their cyber security and being perceived as not in line with peers, or appearing weak.

“We’ve got an accreditation that we gained from Cyber Essentials - the audit and report have to be done as part of that process.” Large business

However, there were instances where cyber security was detailed more thoroughly in corporate reports. One business interviewed aimed their reporting at shareholders, so it was vitally important to go into depth on cyber security to assure them investments were being protected. Aspects of cyber security covered included innovations in the previous year, any new deployments, and training initiatives. They also detailed the number of threats identified in the course of the last twelve months. This was written by cyber security staff, but simplified and edited by the communications department.

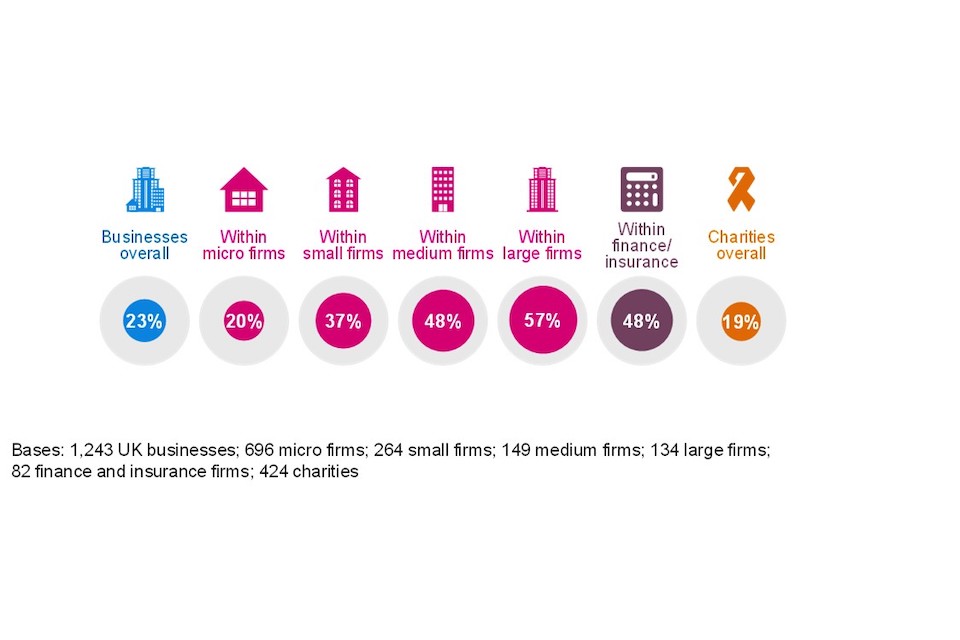

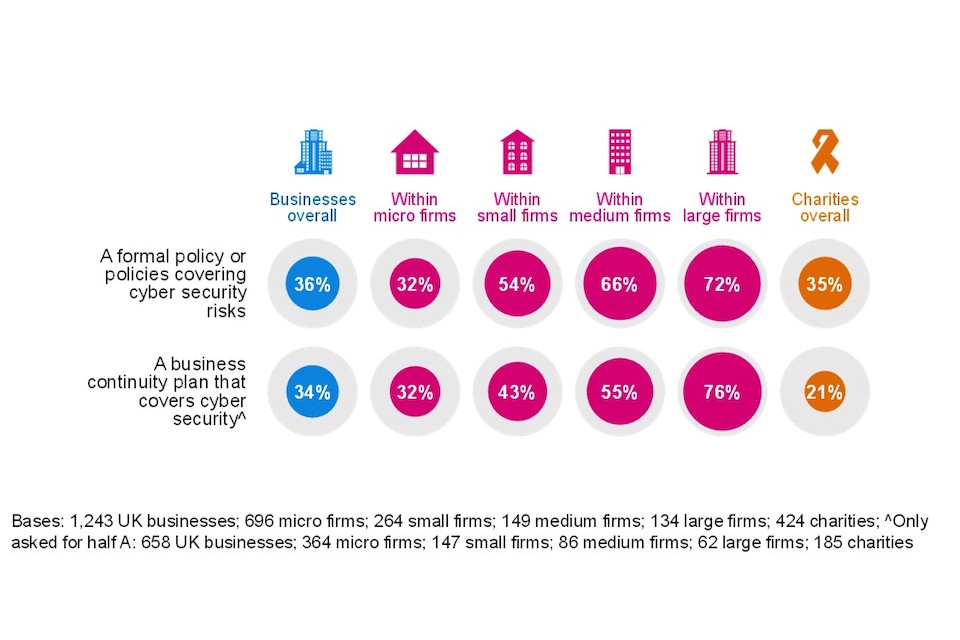

4.2 Cyber security strategies

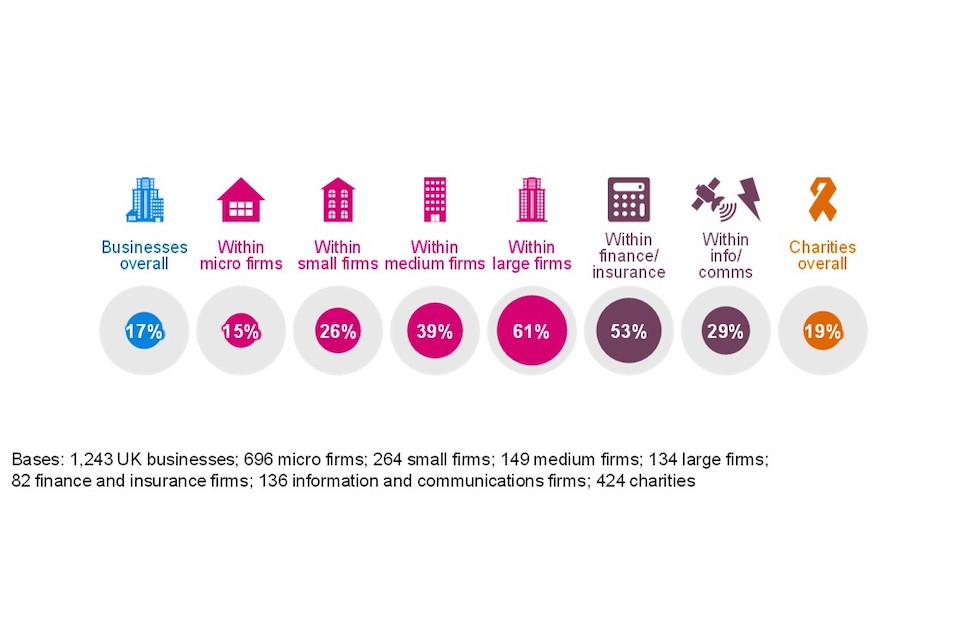

This year we asked organisations for the first time if they had a cyber security strategy, defined as a document that underpins all policies and processes relating to cyber security. We asked follow up questions to better understand the process used to create their cyber strategy, and the approach to cyber security that it outlines. As Figure 4.4 shows, fewer than a quarter of businesses (23%) or charities (19%) have a formal cyber security strategy in place.

Figure 4.4: Organisations that have a formal cyber security strategy

This figure rises to almost half (48%) of medium sized business and is almost six in ten (57%) amongst large businesses. Whilst effective sample sizes are small, cyber security strategies are more often put in place by financial and insurance firms (48%). Among the very largest charities with an income of £5 million or more (41%) the proportion with a formal cyber security strategy is double the charity average (19%).

Among those organisations that do have a cyber security strategy in place, over seven in ten report that this has been reviewed by senior executives / trustees within the last 12 months. This is true of both business (79%) and charities (74%).

Where relevant, five in ten businesses (51%) and four in ten charities (41%) have had their cyber security strategy reviewed by a third party, such as IT or cyber security consultants, or external auditors. This is true of half the micro/small firms (50%) that have a formal cyber security strategy in place, rising to around two-thirds of medium (65%) and large businesses (68%). For businesses that have reviewed their cyber strategy, this is usually part of a wider review (58%) instead of a specific cyber security review (37%). This suggests that cyber security is often perceived or treated as just one area of risk management.

4.3 Insurance against cyber security breaches

Which organisations are insured?

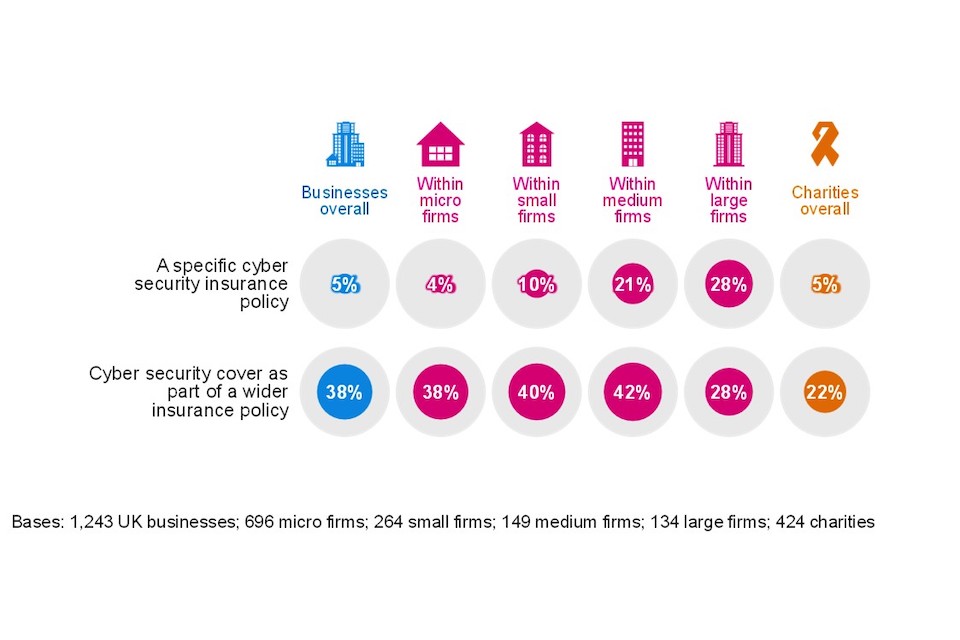

Over four in ten businesses (43%) and almost three in ten charities (27%) report being insured against cyber security risks in some way. These figures are virtually unchanged since 2021 (43% and 29% respectively). The overall figure of 43% in this year’s survey is a clear increase on the 32% in 2020 when the question was introduced, however as only 5 percentage points of the 43 are for a specific cyber security insurance policy this shows that businesses are opting to increase the scope of their current insurance, rather than more proactively seeking cyber cover through an independent insurance policy.

As was the case in 2021 and as Figure 4.5 shows, across all size bands, cyber security insurance is more likely to be through a broader policy, rather than one that is cyber specific. Specific policies are more prevalent among medium (21%) and large firms (28%).

It is worth noting the high level of uncertainty that remains at this question. Among those responsible for cyber security in the private sector, one-fifth (20%) do not know if their employer has any form of cyber security insurance. In charities, this increases to over one-quarter (27%).

Figure 4.5: Percentage of organisations that have the following types of insurance against cyber security risks

As might be expected, insurance cover is more prevalent in the finance and insurance sector itself. Six in ten finance and insurance firms have some sort of coverage against cyber security breaches (60%, vs. 43% overall). Even here, this is not a specific cyber security insurance policy in most cases (only 23% of these firms have a specific policy). Other sectors where over half reported some form of cyber insurance were:

- Professional, scientific, and technical firms (55%)

- retail or wholesale (51%)

Higher-income charities (with £500,000 or more) are more likely than others to have cyber security cover (57%), either as part of a general insurance policy (41% vs. 22% overall) or within a specific policy (16% vs. 5% overall). This becomes a much larger majority among the very high-income charities (70%). Each of these figures is virtually unchanged since 2021.

Making an insurance claim

Of those with some form of cyber insurance, a tiny proportion of businesses and charities report having made an insurance claim to date. It is less than one percent among businesses and two percent of those charities with cyber security insurance in place.

In 2021 seven percent of large businesses with a relevant policy said they had made a claim under their cyber security insurance. This year not a single large business reported making a claim.

Why organisations have cyber insurance and what’s in policies

As in previous years, we asked organisations about their cyber insurance policies. There were a number of reasons that explained why organisations took out insurance and what was in their policies:

- Insurance providers’ expertise on breach recovery was a key reason for taking out a cyber insurance policy. This was to ensure continuity in the event of a disruptive breach. Some policies gave access to legal help and expertise, as well as a forensic analysis of what caused the breach. Insurers were also able to help organisations recover their systems in the event of a breach. Compensation for damages was also mentioned as a benefit to insurance during breach recovery, but this was largely assumed, so did not tend to influence when choosing a policy.